It is a mistake to underestimate Santa Claus. He didn’t get a part in the Bible, but he’s sure a big part of Christmas.

On Christmas Eve there is a children’s service here. It’s one of the biggest of the year. Children and chaos abound, and the atmosphere is charged. We sing, we laugh, and we tell stories of cribs and candles and Christmases past. We also have Santa.

For years I’ve had trouble with Santa. No, it’s not the reindeer parking problems or the resultant pooh… it’s finding Santa himself. It takes a special person to don the red suit, and frankly some of them haven’t been up to it. There’s more to being Santa than sticking out your stomach, chuckling ‘Ho, ho, ho’, and answering smart seven year olds. But – and this is the interesting bit – Santa is never a flop. He never falls from the grace the children extend.

On Santa’s entrance – from the roof of course – the energy levels rise. Whatever he says is listened to. Whatever he does is received with rapt attention. The power of Santa is quite formidable.

Many people take a low view of Santa. He is paraded in every shopping mall in the country encouraging people to buy, and buy more. He doesn’t say, “Pay off that car you drive” or “pay that phone bill”. No, he’s saying buy new and buy now things we know we could do without. Santa is a slave of rampant consumerism.

Then there is the bribery brigade. “Listen boys and girls, if you aren’t good [read: do what I say] then Santa won’t come this year.” Santa’s morality is reduced to the suspect morality of these parents. Everything in life has to be earned. Including love. Including Santa.

Max, my neighbour, also takes a low view of what he calls “the Santa myth”. He objects to the portrayal of vertically challenged people merrily working in cramped sweat shop conditions. He objects to reindeer being used as promotional aids with no benefits accruing to the threatened herds of Northern Europe. He objects to an obese elderly man being given, firstly, license to enter any home or premise, secondly, a monopoly on the disbursement of gifts, and thirdly, an annual parade in his honour. Santa to him is a symbol of inequity.

The original Santa was, of course, a saint. Dear old wealthy Bishop Nic lived in the ancient city of Myra and gave generously to others. One story has it that an angel visited him one night and said, “Nicholas, you must take a bag of gold to the pawnbroker’s, for he is very poor and has three daughters. Unless they have a dowry, they will be sold into slavery.” Nic took the gold and rushed to the pawnbroker’s house where he discreetly dropped it through a window. Naturally, the parents were overjoyed; now their eldest could marry.

As you would expect in a good story this angelic visitation and discreet dropping of gold happened three times. But on the third and last drop the Pawnbroker, curious to discover the identity of his benefactor, locked all the windows of the house. Nic not being short of ideas climbed up on the roof and deposited the bag down the chimney.

It’s a story about sympathy for those in poverty, about practical assistance, and innovative delivery systems. It’s about compassion. It’s about shedding wealth. It’s about the virtue of anonymous giving – a virtue that in our modern world of sponsorship seems almost quaint.

Personally I take a high view of Santa, and not just to infuriate my neighbour Max [which it does]. I simply believe in Santa Claus. And, like most beliefs, it has been refined and tempered by experience, especially year by year sitting with children at Christmas and trying to explain in simple, precise language the meaning of life, faith, and flying sleighs.

There comes a time in most children’s lives when some of the mathematics of Santa seem insurmountable. Consider the number of children in this city, the quantity and size of presents, the dimensions of your above average sleigh, the distance from Auckland to the North Pole, the aerodynamic potential of reindeer… So, inevitably the questions arise: “How come…?” “How does he do that?” And, looking at me as though I was deranged, “Do you actually believe in Santa Claus?”

If the inquisitor is worth their salt they won’t stop there. “What about the down the chimney bit eh?” “Yep,” I reply, “I’m into it.” “Look Glynn,” my young friend continues, “our chimney is designed for someone who only eats lettuce. It has a metal pipe of some 20 centimetres in diameter. Are you telling me that Santa can squeeze down that?”

“Well,” I respond, girding myself for the challenge, “tell me how your favourite music group can sing their stuff through cyberspace, enter your computer, and morph themselves onto a CD for you to enjoy whenever? And you think a bit of chimney pipe is a problem?” Around now my young friend will roll their eyes, code for ‘my silence is not my assent’. Failure to appreciate the fertile imagination is as big a problem in our society as consumerism.

The better questions for the young inquirer to ask are about meaning. For Santa means giving. Giving to others. Giving to those we don’t know. Giving with no strings attached - including no reciprocating gifts.

Santa is about dreaming that nothing is impossible when it comes to helping and sharing. No elf, no chimney, no amount of snow, or consumerism, or cynicism, is going to stop it. This is why I believe in Santa Claus.

The Santa saga is more powerful than any factual findings by the geek who sat for three consecutive Christmas Eves with a telescope and camcorder on a rooftop. Santa inspires and encourages the best in humanity, the best in you and me – selfless giving to others.

Christmas is simple really: Give what you can and then some. Don’t believe in the barriers to giving. Set your imagination free. Dream of a world where all can have enough and be satisfied with it.

These are the gifts that Santa brings time and again, time and again.

12/23/2006

Christmas Thoughts - Mary

“With God all things are possible,” said the angelic Gabriel to a distressed Mary. Viewers of the recent movie Nativity might paraphrase Gabriel’s message: “With technology, cinematic license, and funding all religious fantasies are possible.”

Nativity is a marked improvement on its forebears, particularly in its portrayal of the repressive governance of Palestine and the patriarchal culture that impacted on women. However Nativity reminded me of a parish Christmas pageant, uncritically splicing the two infancy narratives together and using unbelievable tricks to explain the miraculous. Unlike the parish pageant though Nativity masquerades as history.

Liberal scholars have for decades told us that most of the supposed facts of the nativity are fictions. Angels, wise men, heavenly hosts, the census, Bethlehem… are all part of the story-telling craft, weaving meanings derived from Jesus’ life back into his birth. It makes for great stories, encapsulates great truths, but is lousy history.

As for the paternity of Jesus, these liberal scholars denounced the biological miracle thesis that Nativity went to some length to replicate. We all know that fertilized eggs don’t drop from the sky into wombs, despite what some in the Vatican think. Joseph, said these scholars, was the most likely father.

Scholarship has since moved on, now less concerned about history and more concerned about what the texts actually say. It makes no sense, for example, for both Matthew and Luke to sow doubt about Jesus’ paternity if Joseph was his actual father. The scandal that accompanied the pregnancy, as the movie Nativity showed, would have diminished if Joseph had owned up. Indeed the pregnancy of a betrothed girl by her fiancé was viewed as more positive than negative, for it was thought to guarantee children and ensure the male line.

Who then was the father? For those who like to use God, as the movie does, to explain the supposed unexplainable please note two things. Firstly, the words used by Gabriel “come upon” and “overshadow” have no sexual connotations. It’s not saying that Mary had sex with the Holy Spirit. Secondly, divine paternity and human paternity are not mutually exclusive. God is the power of all life. In other words, as with King David being called “Son of God”, it is possible to have human parents and still be hailed as of divine origin.

There has been growing acceptance during the last decades of the validity of Jane Schaberg’s work. Jane teaches at a Roman Catholic university. She posits that Mary was seduced or raped, a child was conceived, and that God owned, and declared as blessed, both mother and babe. When the Magnificat sings that God has looked with favour on the lowliness of Mary, and the Greek word for lowliness usually is translated ‘humiliation’[i], one has to ask how she was humiliated. Illegitimacy, despite the indoctrination of multiple Christmas pageants, is probably the answer.

You can read the rest of my article at http://www.stmatthews.org.nz/?sid=74&id=681

Further reading:

1. Schaberg, Jane The Illegitimacy of Jesus, Sheffield Phoenix Press 2006.

2. Summary of Schaberg’s work http://www.pinn.net/~sunshine/book-sum/illegit.html

3. Reilly, Frank “Jane Schaberg, Raymond E. Brown, and the Problem of the Illegitimacy of Jesus” http://muse.jhu.edu/about/publishers/indiana

4. Spong, John Born Of A Woman: A bishop rethinks the birth of Jesus, New York Harper Collins 1992

[i] The word is used in Genesis 34:2, Judges 19:24 and 20:5, II Kings 13:12, 14, 22, and 32; and Lamentations 5:11. These passages all address rapes.

Nativity is a marked improvement on its forebears, particularly in its portrayal of the repressive governance of Palestine and the patriarchal culture that impacted on women. However Nativity reminded me of a parish Christmas pageant, uncritically splicing the two infancy narratives together and using unbelievable tricks to explain the miraculous. Unlike the parish pageant though Nativity masquerades as history.

Liberal scholars have for decades told us that most of the supposed facts of the nativity are fictions. Angels, wise men, heavenly hosts, the census, Bethlehem… are all part of the story-telling craft, weaving meanings derived from Jesus’ life back into his birth. It makes for great stories, encapsulates great truths, but is lousy history.

As for the paternity of Jesus, these liberal scholars denounced the biological miracle thesis that Nativity went to some length to replicate. We all know that fertilized eggs don’t drop from the sky into wombs, despite what some in the Vatican think. Joseph, said these scholars, was the most likely father.

Scholarship has since moved on, now less concerned about history and more concerned about what the texts actually say. It makes no sense, for example, for both Matthew and Luke to sow doubt about Jesus’ paternity if Joseph was his actual father. The scandal that accompanied the pregnancy, as the movie Nativity showed, would have diminished if Joseph had owned up. Indeed the pregnancy of a betrothed girl by her fiancé was viewed as more positive than negative, for it was thought to guarantee children and ensure the male line.

Who then was the father? For those who like to use God, as the movie does, to explain the supposed unexplainable please note two things. Firstly, the words used by Gabriel “come upon” and “overshadow” have no sexual connotations. It’s not saying that Mary had sex with the Holy Spirit. Secondly, divine paternity and human paternity are not mutually exclusive. God is the power of all life. In other words, as with King David being called “Son of God”, it is possible to have human parents and still be hailed as of divine origin.

There has been growing acceptance during the last decades of the validity of Jane Schaberg’s work. Jane teaches at a Roman Catholic university. She posits that Mary was seduced or raped, a child was conceived, and that God owned, and declared as blessed, both mother and babe. When the Magnificat sings that God has looked with favour on the lowliness of Mary, and the Greek word for lowliness usually is translated ‘humiliation’[i], one has to ask how she was humiliated. Illegitimacy, despite the indoctrination of multiple Christmas pageants, is probably the answer.

You can read the rest of my article at http://www.stmatthews.org.nz/?sid=74&id=681

Further reading:

1. Schaberg, Jane The Illegitimacy of Jesus, Sheffield Phoenix Press 2006.

2. Summary of Schaberg’s work http://www.pinn.net/~sunshine/book-sum/illegit.html

3. Reilly, Frank “Jane Schaberg, Raymond E. Brown, and the Problem of the Illegitimacy of Jesus” http://muse.jhu.edu/about/publishers/indiana

4. Spong, John Born Of A Woman: A bishop rethinks the birth of Jesus, New York Harper Collins 1992

[i] The word is used in Genesis 34:2, Judges 19:24 and 20:5, II Kings 13:12, 14, 22, and 32; and Lamentations 5:11. These passages all address rapes.

Christmas Thoughts - Shepherds

There were some hands camped out in a paddock nearby, keeping an eye on their mob of sheep that night. Their eyes popped out on stalks when an angel breezed by and lit up the sky like Xmas-in-the-Park.

“Jeepers!” they said.

The angel replied, “Stop looking like a bunch of stunned mullets. Let me tell you what’s going down. Today in a one-horse town over the hill a kid has been born. No ordinary ankle-biter. Gonna turn the world upside down. You’ll find him wrapped in a blankie and lying in a feed-trough.”

And before you could say, “Gimme a break!” the whole sky was filled with more angels than Aucklanders in a traffic jam, and making just about as much noise.

When eventually the whole show had moved on, the hands looked at one another: “Reckon we’d better check this out.”

The Christmas story is more than a slice of ancient history. Its power reaches across time and culture to speak even in our language. It’s a story that can both comfort and challenge.

The country location of this angelic announcement was offensive. The appearance to the shepherds happened not in the holy temple in Jerusalem where religious, financial, and political power coalesced. Rather it happened in some unnamed rural setting, among people of little wealth.

The country location tells us that God’s business doesn’t revolve around the ‘Wellingtons’ or ‘Washingtons’. Nor is God closeted, and cosseted, in fancy Cathedrals, colleges or holy cloisters. God is out and about. God is not just in flash places, but also round the back, in the kitchen of life, among ordinary people, pitching in, using the tea towel, and having a natter.

In 1850 John Everett Millais, one of the English artists known as the Pre-Raphaelites, painted his Christ In The House Of His Parents. He tried to realistically depict the lowly life of a carpenter and his family – tools and wood shavings clutter the earthen floor.

The painting met with a storm of protest. Fancy the idea of Jesus living in such an unhealthy and primitive environment!! Millais threatened the boundaries of the class-structure still firmly embedded in 19th century English society.

The agrarian location of the angelic visit caused similar offence.

Shepherds were likewise offensive. While the word ‘shepherd’ may evoke Christmas card and nativity pictures of sandaled saints adorned in white headdress, caring souls with lambs tucked under their arms… the reality was otherwise.

Shepherds were a dodgy lot. Shifty. You wouldn’t buy a used camel off them – you might burn yourself on the bridle! They were known for their fencing, and I’m not talking about the sport or No. 8 wire. Maybe the words ‘crook’ and ‘fleeced’ originate from those times? Shepherds were social undesirables. In general they had the social standing of our tow-truck drivers or repossession agents.

The insertion of shepherds in the birth narrative alludes to the connection between the baby Jesus and the great King David, who was called from tending sheep to ascend the dizzy heights of monarchy. It’s the old poverty to power, or rags to riches theme. This little baby, born in a Bethlehem shed, was the one who would be great.

Yet the theme, as you read the whole gospel, works in reverse. The greatness of God, as seen in this baby and the adult Jesus, chooses to associate with marginal and undesirable people. Jesus was building an upside-down kingdom full of nuisances and nobodies. His vision was for a huge Christmas party, with plenty of good tucker – lamb, Pavlova, mince pies, joy, and laughter - to go around. A party where everyone, particularly those who were vulnerable, suffering in poverty, or despised by religion and society were made especially welcome. The sign on the door read: “Losers Welcome”. And the winners didn’t like it.

The shepherd story has a simple message really. God turns up in the most unlikely places and among the most unlikely people and saying the most unlikely things. You’ll probably find God round the back rather than out front, pulling weeds rather than pulling rank, looking grubby rather than looking grand. If God can visit shepherds God can even visit you, and just might.

If you go looking for God here are some hints: Firstly, avoid powerful people who think they can stuff God in their pockets. Secondly, don’t discount those in trouble with the law or who tell you about seeing white-winged apparitions. Thirdly, be mindful of the little things in life, like babies and animals. That which is small, local, fragile, and unpredictable is, in God’s upside-down scheme of things, often where hope is to be found.

“Jeepers!” they said.

The angel replied, “Stop looking like a bunch of stunned mullets. Let me tell you what’s going down. Today in a one-horse town over the hill a kid has been born. No ordinary ankle-biter. Gonna turn the world upside down. You’ll find him wrapped in a blankie and lying in a feed-trough.”

And before you could say, “Gimme a break!” the whole sky was filled with more angels than Aucklanders in a traffic jam, and making just about as much noise.

When eventually the whole show had moved on, the hands looked at one another: “Reckon we’d better check this out.”

The Christmas story is more than a slice of ancient history. Its power reaches across time and culture to speak even in our language. It’s a story that can both comfort and challenge.

The country location of this angelic announcement was offensive. The appearance to the shepherds happened not in the holy temple in Jerusalem where religious, financial, and political power coalesced. Rather it happened in some unnamed rural setting, among people of little wealth.

The country location tells us that God’s business doesn’t revolve around the ‘Wellingtons’ or ‘Washingtons’. Nor is God closeted, and cosseted, in fancy Cathedrals, colleges or holy cloisters. God is out and about. God is not just in flash places, but also round the back, in the kitchen of life, among ordinary people, pitching in, using the tea towel, and having a natter.

In 1850 John Everett Millais, one of the English artists known as the Pre-Raphaelites, painted his Christ In The House Of His Parents. He tried to realistically depict the lowly life of a carpenter and his family – tools and wood shavings clutter the earthen floor.

The painting met with a storm of protest. Fancy the idea of Jesus living in such an unhealthy and primitive environment!! Millais threatened the boundaries of the class-structure still firmly embedded in 19th century English society.

The agrarian location of the angelic visit caused similar offence.

Shepherds were likewise offensive. While the word ‘shepherd’ may evoke Christmas card and nativity pictures of sandaled saints adorned in white headdress, caring souls with lambs tucked under their arms… the reality was otherwise.

Shepherds were a dodgy lot. Shifty. You wouldn’t buy a used camel off them – you might burn yourself on the bridle! They were known for their fencing, and I’m not talking about the sport or No. 8 wire. Maybe the words ‘crook’ and ‘fleeced’ originate from those times? Shepherds were social undesirables. In general they had the social standing of our tow-truck drivers or repossession agents.

The insertion of shepherds in the birth narrative alludes to the connection between the baby Jesus and the great King David, who was called from tending sheep to ascend the dizzy heights of monarchy. It’s the old poverty to power, or rags to riches theme. This little baby, born in a Bethlehem shed, was the one who would be great.

Yet the theme, as you read the whole gospel, works in reverse. The greatness of God, as seen in this baby and the adult Jesus, chooses to associate with marginal and undesirable people. Jesus was building an upside-down kingdom full of nuisances and nobodies. His vision was for a huge Christmas party, with plenty of good tucker – lamb, Pavlova, mince pies, joy, and laughter - to go around. A party where everyone, particularly those who were vulnerable, suffering in poverty, or despised by religion and society were made especially welcome. The sign on the door read: “Losers Welcome”. And the winners didn’t like it.

The shepherd story has a simple message really. God turns up in the most unlikely places and among the most unlikely people and saying the most unlikely things. You’ll probably find God round the back rather than out front, pulling weeds rather than pulling rank, looking grubby rather than looking grand. If God can visit shepherds God can even visit you, and just might.

If you go looking for God here are some hints: Firstly, avoid powerful people who think they can stuff God in their pockets. Secondly, don’t discount those in trouble with the law or who tell you about seeing white-winged apparitions. Thirdly, be mindful of the little things in life, like babies and animals. That which is small, local, fragile, and unpredictable is, in God’s upside-down scheme of things, often where hope is to be found.

12/12/2006

Defying Sense

You get some cents. But it also defies sense. Why should you receive money for teeth? Teeth aren’t recyclable or usable in a commercial sense. There is no economic reason for the recompense.

Jim, my friend, is also suspicious about the recompense. “Why,” he asks me, “must we mark each transitional stage in a child’s life with gifts? We give them gifts at birth, baptism, and birthdays. Money, money, money. Why can’t we value children differently than this? Isn’t the Tooth Fairy just a manifestation of capitalism: everything has a price - even teeth!”

There is some sense in what Jim says. Yes, we could try and close down the whole gift-giving industry putting the Tooth Fairy, Santa, the Elves, and hundreds of Warehouse employees out of work. We would also close down part of ourselves. The part that wants to give to others.

In Tooth Fairy thought the cents, the coin under the pillow, is undeserved. It is gift. It is not earned. The tooth doesn’t earn money. But the gift does acknowledge the pain of the past. And it is a vehicle for the giver to express practical compassion.

The role of Tooth Fairy non-sense is to help us live out and encourage each other in compassion, undeserved giving, and providing recompense for pain and hardship. Justice needs to be cultivated, and at some point needs to be about cents.

Jim, my friend, is also suspicious about the recompense. “Why,” he asks me, “must we mark each transitional stage in a child’s life with gifts? We give them gifts at birth, baptism, and birthdays. Money, money, money. Why can’t we value children differently than this? Isn’t the Tooth Fairy just a manifestation of capitalism: everything has a price - even teeth!”

There is some sense in what Jim says. Yes, we could try and close down the whole gift-giving industry putting the Tooth Fairy, Santa, the Elves, and hundreds of Warehouse employees out of work. We would also close down part of ourselves. The part that wants to give to others.

In Tooth Fairy thought the cents, the coin under the pillow, is undeserved. It is gift. It is not earned. The tooth doesn’t earn money. But the gift does acknowledge the pain of the past. And it is a vehicle for the giver to express practical compassion.

The role of Tooth Fairy non-sense is to help us live out and encourage each other in compassion, undeserved giving, and providing recompense for pain and hardship. Justice needs to be cultivated, and at some point needs to be about cents.

12/01/2006

Simple Theology - courtesy of the Fairy

There is a myth that most children discard somewhere around the age of eight: the Tooth Fairy. They write off the Tooth Fairy as nonsense. The cents gained from the story have been spent. It was good while it lasted. Now on to other things. It’s like a cell-phone with no battery: throw it into a baby’s toy box and forget it!

I like the Tooth Fairy. She or he performs a simple function, for no apparent reasons, inspired by no apparent motive, save to compensate children for the pain they have endured in shedding a tooth. The Tooth Fairy stands for justice.

There are many questions one could ask of the Tooth Fairy and her/his admirers. A seven year old interrogates his father:

“Dad, prove the Tooth Fairy exists?”

“Well, Johnny your teeth disappear from under your pillow and money appears.”

“I know. You do it.”

“So, you think I’m a fairy?”

“Ahhh.. Yes.”

“Well, I know it seems difficult to believe but the Tooth Fairy is bigger than me.”

And so continues the dance between logic and illogic, between sense and nonsense.

The more sophisticated seven year old moves the questions up a notch:

“Dad, what use does the Tooth Fairy have for teeth?”

“Dad, what’s the going rate for teeth and who sets the rate?” [I have yet to hear an adult-to-adult conversation on this one].

“Dad, why must my tooth go under a pillow? Why not leave it beside my bed? Why’s the Fairy into pillows?”

“Dad, why does the Tooth Fairy leave money?”

The last question, in particular, is one that, similar to the opening of a curtain, allows the world to be seen differently. The horizon starts to expand. The Tooth Fairy leaves money as an acknowledgement that children suffer pain. That such suffering is as unfair as it is inevitable. The Tooth Fairy is a mythic figure of compassion and justice.

Tooth Fairy theology, when you think about it, has some great advantages:

1. It’s simple. Teeth for money. Only a pillow required. No sophisticated belief system with creeds, clergy, and churches.

2. It deftly avoids the politics of dress, gender, body, and religion. Our imaginations shape the Tooth Fairy. S/he doesn’t need a historical, cultural context, or a pouncy red suit with matching beard and reindeer, in order to be authentic. S/he can just do their own thing: conservative or camp, trendy or trashy. The Tooth Fairy fits every size, every political persuasion. S/he is user-friendly.

3. The Tooth Fairy has a single message: practical recompense for pain.

I like the Tooth Fairy. She or he performs a simple function, for no apparent reasons, inspired by no apparent motive, save to compensate children for the pain they have endured in shedding a tooth. The Tooth Fairy stands for justice.

There are many questions one could ask of the Tooth Fairy and her/his admirers. A seven year old interrogates his father:

“Dad, prove the Tooth Fairy exists?”

“Well, Johnny your teeth disappear from under your pillow and money appears.”

“I know. You do it.”

“So, you think I’m a fairy?”

“Ahhh.. Yes.”

“Well, I know it seems difficult to believe but the Tooth Fairy is bigger than me.”

And so continues the dance between logic and illogic, between sense and nonsense.

The more sophisticated seven year old moves the questions up a notch:

“Dad, what use does the Tooth Fairy have for teeth?”

“Dad, what’s the going rate for teeth and who sets the rate?” [I have yet to hear an adult-to-adult conversation on this one].

“Dad, why must my tooth go under a pillow? Why not leave it beside my bed? Why’s the Fairy into pillows?”

“Dad, why does the Tooth Fairy leave money?”

The last question, in particular, is one that, similar to the opening of a curtain, allows the world to be seen differently. The horizon starts to expand. The Tooth Fairy leaves money as an acknowledgement that children suffer pain. That such suffering is as unfair as it is inevitable. The Tooth Fairy is a mythic figure of compassion and justice.

Tooth Fairy theology, when you think about it, has some great advantages:

1. It’s simple. Teeth for money. Only a pillow required. No sophisticated belief system with creeds, clergy, and churches.

2. It deftly avoids the politics of dress, gender, body, and religion. Our imaginations shape the Tooth Fairy. S/he doesn’t need a historical, cultural context, or a pouncy red suit with matching beard and reindeer, in order to be authentic. S/he can just do their own thing: conservative or camp, trendy or trashy. The Tooth Fairy fits every size, every political persuasion. S/he is user-friendly.

3. The Tooth Fairy has a single message: practical recompense for pain.

11/19/2006

'Servant Leadership'??

The word “servant” or “serving” needs to be carefully used in relation to Church leadership. As a friend once said, “When I see cleaners, waitresses, and rubbish collectors becoming bishops and priests I’ll believe the Church has servants as leaders.” He has a point. ‘Servant’ has socio-political implications.

What do we mean in the Church by the word ‘serving’? Does it mean that our priest should be on every committee? I would say that reflects an inability to trust others. Does it mean that our priest knows every parishioner’s needs, and where possible attends to them? I think it is the vocation of every Christian to be a good neighbour and care for one another. By expecting the priest to do it we are neglecting our baptismal vocation.

I remember one vicar who for twenty years had a wonderful reputation among his parishioners. He was always there for them, always caring, always available. However in the 20 years he served that parish both his family and his health fell apart. He had succumbed to an uncritical understanding of ‘servant leadership’. There’s little chance that any oppressive government will crucify clergy like him because they’ve already laid down their lives for the Church!

Self-care is not optional. You live what you are. The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality. If reality is solely your business or your Church then you have failed to understand what spirituality is and the importance of the transformative love called God permeating all of your life and relationships. I think a priest’s job description should be simply “To pray Jesus’ vision into being”. Period. But please don’t think I mean something passive when I use the word ‘pray’.

When you are, like me, a recipient of privilege (and it is a privilege to lead) you have the obligation to use that privilege and its power wisely. This is what ‘serving’ is. ‘Serving’ doesn’t mean necessarily doing the dishes. Often it is harder to make small talk with the dignitaries out front than pick up a tea towel out back. ‘Serving’ is about being conscious of the good fortune and grace bestowed upon you, and treating all others with grace and dignity as equals. The opposite is arrogance, which unfortunately is all too common.

The task of the Christian leader is to articulate a vision and to lead people in the transformation of society in line with that vision. Further, and intimately connected with this, is the ability to live and engender the spirituality that will sustain both the struggle and its outcome. This is how Jesus led. When he died he left others to manage. Thankfully some of them had the courage and tenacity to lead.

What do we mean in the Church by the word ‘serving’? Does it mean that our priest should be on every committee? I would say that reflects an inability to trust others. Does it mean that our priest knows every parishioner’s needs, and where possible attends to them? I think it is the vocation of every Christian to be a good neighbour and care for one another. By expecting the priest to do it we are neglecting our baptismal vocation.

I remember one vicar who for twenty years had a wonderful reputation among his parishioners. He was always there for them, always caring, always available. However in the 20 years he served that parish both his family and his health fell apart. He had succumbed to an uncritical understanding of ‘servant leadership’. There’s little chance that any oppressive government will crucify clergy like him because they’ve already laid down their lives for the Church!

Self-care is not optional. You live what you are. The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality. If reality is solely your business or your Church then you have failed to understand what spirituality is and the importance of the transformative love called God permeating all of your life and relationships. I think a priest’s job description should be simply “To pray Jesus’ vision into being”. Period. But please don’t think I mean something passive when I use the word ‘pray’.

When you are, like me, a recipient of privilege (and it is a privilege to lead) you have the obligation to use that privilege and its power wisely. This is what ‘serving’ is. ‘Serving’ doesn’t mean necessarily doing the dishes. Often it is harder to make small talk with the dignitaries out front than pick up a tea towel out back. ‘Serving’ is about being conscious of the good fortune and grace bestowed upon you, and treating all others with grace and dignity as equals. The opposite is arrogance, which unfortunately is all too common.

The task of the Christian leader is to articulate a vision and to lead people in the transformation of society in line with that vision. Further, and intimately connected with this, is the ability to live and engender the spirituality that will sustain both the struggle and its outcome. This is how Jesus led. When he died he left others to manage. Thankfully some of them had the courage and tenacity to lead.

11/17/2006

Management or Leadership

Two stories, one of good management and one of good leadership:

“An influential British politician kept pestering Disraeli for a baronetcy. The Prime Minister could not see his way to obliging the man but he managed to refuse him without hurting his feelings. He said, “I am sorry I cannot give you a baronetcy, but I can give you something better: you can tell your friends that I offered you the baronetcy and that you turned it down.”[i]

Good management. Now for good leadership:

“Of the great Zen Master Rinzai it was said that each night the last thing he did before he went to bed was let out a great belly laugh that resounded through the corridors and was heard in every building of the monastery grounds. And the first thing he did when he woke at dawn was burst into peals of laughter so loud they woke up every monk no matter how deep his slumber.”[ii]

Good leadership. A leader defines reality - both for him/herself and for others. That’s what that laugh was doing. How much laughter is there in your Church or workplace?

[i] De Mello, A. The Prayer Of The Frog, Anand : Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, 1988, p.154

[ii] De Mello, A. The Prayer Of The Frog, p.172.

“An influential British politician kept pestering Disraeli for a baronetcy. The Prime Minister could not see his way to obliging the man but he managed to refuse him without hurting his feelings. He said, “I am sorry I cannot give you a baronetcy, but I can give you something better: you can tell your friends that I offered you the baronetcy and that you turned it down.”[i]

Good management. Now for good leadership:

“Of the great Zen Master Rinzai it was said that each night the last thing he did before he went to bed was let out a great belly laugh that resounded through the corridors and was heard in every building of the monastery grounds. And the first thing he did when he woke at dawn was burst into peals of laughter so loud they woke up every monk no matter how deep his slumber.”[ii]

Good leadership. A leader defines reality - both for him/herself and for others. That’s what that laugh was doing. How much laughter is there in your Church or workplace?

[i] De Mello, A. The Prayer Of The Frog, Anand : Gujarat Sahitya Prakash, 1988, p.154

[ii] De Mello, A. The Prayer Of The Frog, p.172.

11/16/2006

Jesus not managing contd.

Jesus promoted a political and spiritual vision of an upside down kingdom where the last are first and the first slaves. It is a place where the CEO’s wash the feet of the unemployed. It is a place where the outsiders are in, and the insiders choose to be out. It is a place where the 99 sheep are deserted in order that the lost one is found. It is a place where the despicable find a home.

In this vision Jesus, despite the wishful thinking of many of his followers, will not sit on a throne with his trusted lieutenants beside him, sycophants serving him, and his heavenly army available in the wings. Rather it is a vision that led to the cross. The forces of oppression nailed him. Two thieves were beside him. Roman soldiers took his meagre assets. His only faithful ‘army’ were a few wailing women. Siding with outsiders made Jesus an outsider. He died an outsider’s death. By threatening the powerful Jesus became a threat. There is a terrible cost to ignoring ideological safety.

The leadership of Jesus demanded something of his followers, and demands something of us. It demands commitment to making his vision a reality in our lives. As Ghandi said, “We must become the change we want to see.” It demands a commitment to stand with outsiders and both criticise and seek to dismantle the structures that keep them there. When you stand with outsiders in time you become one.

Most of what is called leadership today in the Church is a blend of management and leadership. We need both. The worry is that, firstly, in the order to maintain ‘productivity’ we will nurture risk-adverse strategies. ‘Keep doing the same things but just do them better!’ And secondly we will encourage our clergy to be managers more than leaders. Despite rhetoric to the contrary the Church employs pastors who primarily serve its institutional needs.

In this vision Jesus, despite the wishful thinking of many of his followers, will not sit on a throne with his trusted lieutenants beside him, sycophants serving him, and his heavenly army available in the wings. Rather it is a vision that led to the cross. The forces of oppression nailed him. Two thieves were beside him. Roman soldiers took his meagre assets. His only faithful ‘army’ were a few wailing women. Siding with outsiders made Jesus an outsider. He died an outsider’s death. By threatening the powerful Jesus became a threat. There is a terrible cost to ignoring ideological safety.

The leadership of Jesus demanded something of his followers, and demands something of us. It demands commitment to making his vision a reality in our lives. As Ghandi said, “We must become the change we want to see.” It demands a commitment to stand with outsiders and both criticise and seek to dismantle the structures that keep them there. When you stand with outsiders in time you become one.

Most of what is called leadership today in the Church is a blend of management and leadership. We need both. The worry is that, firstly, in the order to maintain ‘productivity’ we will nurture risk-adverse strategies. ‘Keep doing the same things but just do them better!’ And secondly we will encourage our clergy to be managers more than leaders. Despite rhetoric to the contrary the Church employs pastors who primarily serve its institutional needs.

11/12/2006

Embracing Life

To embrace and enjoy life is a holy act. Here are a few ideas about how we might do that.

Firstly, make time to stop. There is a child’s road safety maxim to be recited on the kerbside: “Stop, look, and listen.” This saying could equally be applied to those on a spiritual journey. We need to stop when the pressure of life says go. We need to look when we are told to act. And we need to listen when we are being exhorted to speak.

Cycling around the waterfront in the morning, as I often do - penance for all those pastries - it only takes a few moments to stop, dismount, look, breath deeply, listen, say “Gee, its good to be alive”, and then remount and cycle off.

In this busy, noisy world we need the courage to pause and give time to our soul.

Secondly, make time for the earth. Remember the days when most rural towns had a bend in the road when metallic debris was discarded. There was a belief that rubbish would decompose or rust away. The earth would cleanse and renew itself.

That belief is now dead and gone. We now know that we must care for the earth like we care for our aging parents. We can’t presume that the earth will always be able to do what it once did. To be faithful to life requires faithfulness to that which nurtures life’s plants, animals, water, and climate.

Thirdly, make time for outsiders. There are numerous people who feel themselves to be outside of the boundaries of ‘normal’. Whether it is due to wealth, health, sexuality, race, or circumstance, they experience life very differently and often oppressively.

We need to nurture the kindness that steps over or around barriers. ‘Normal’ is a word we need to be wary of. Kindness is a word we need to put into practice. Smiling at people, saying ‘Hi’, communicates that they matter. It also conveys the hope that we all will become better more hospitable neighbours to each other.

Lastly, make time for humour. Absurd and ludicrous things happen every day. We just need to pause and let that tickle touch our funny bone.

I remember once receiving a letter from a misguided environmentalist concerned about the impact of burying bodies in a cemetery. Being the curator of a cemetery at the time I responded in a somewhat warped fashion commenting upon the spirituality of worms. Imagine my amazement when I received an additional letter from the lady taking worm religion very seriously. I hope, and like to believe, that she was smiling when she wrote it.

Make time to laugh.

So let us enjoy and embrace life by remembering what is faithfully worth preserving: our soul, our earth, our hospitality, and our humour.

Firstly, make time to stop. There is a child’s road safety maxim to be recited on the kerbside: “Stop, look, and listen.” This saying could equally be applied to those on a spiritual journey. We need to stop when the pressure of life says go. We need to look when we are told to act. And we need to listen when we are being exhorted to speak.

Cycling around the waterfront in the morning, as I often do - penance for all those pastries - it only takes a few moments to stop, dismount, look, breath deeply, listen, say “Gee, its good to be alive”, and then remount and cycle off.

In this busy, noisy world we need the courage to pause and give time to our soul.

Secondly, make time for the earth. Remember the days when most rural towns had a bend in the road when metallic debris was discarded. There was a belief that rubbish would decompose or rust away. The earth would cleanse and renew itself.

That belief is now dead and gone. We now know that we must care for the earth like we care for our aging parents. We can’t presume that the earth will always be able to do what it once did. To be faithful to life requires faithfulness to that which nurtures life’s plants, animals, water, and climate.

Thirdly, make time for outsiders. There are numerous people who feel themselves to be outside of the boundaries of ‘normal’. Whether it is due to wealth, health, sexuality, race, or circumstance, they experience life very differently and often oppressively.

We need to nurture the kindness that steps over or around barriers. ‘Normal’ is a word we need to be wary of. Kindness is a word we need to put into practice. Smiling at people, saying ‘Hi’, communicates that they matter. It also conveys the hope that we all will become better more hospitable neighbours to each other.

Lastly, make time for humour. Absurd and ludicrous things happen every day. We just need to pause and let that tickle touch our funny bone.

I remember once receiving a letter from a misguided environmentalist concerned about the impact of burying bodies in a cemetery. Being the curator of a cemetery at the time I responded in a somewhat warped fashion commenting upon the spirituality of worms. Imagine my amazement when I received an additional letter from the lady taking worm religion very seriously. I hope, and like to believe, that she was smiling when she wrote it.

Make time to laugh.

So let us enjoy and embrace life by remembering what is faithfully worth preserving: our soul, our earth, our hospitality, and our humour.

11/09/2006

Jesus didn't manage

“Managers are people who do things right, while leaders are people who do the right thing.”

Jesus was a leader, not a manager.

Good management is essential in any organization. People need to be heard and understood. Good processes, protocols, and safety provisions need to be in place. Conflict needs to be mediated and resolved. Employees and clients’ hopes and expectations need to be taken seriously. Good management usually leads to increased productivity and profit. This is what many people understand to be leadership.

There is no evidence in the biblical texts that Jesus was a manager. There are few stories of him patiently mediating in conflicts between the disciples; or emphatically caring for those who gave up their jobs and businesses to follow him; or sitting down and listening to the hopes and fears of his followers. Commentators who believe Jesus pastorally coached his disciples are largely arguing from what is unsaid in the texts rather than what is said.

However there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that Jesus lived and preached a vision, and challenged others to follow him.

I think the Church has a bad habit of trying to domesticate Jesus. It paints him as meek, mild, and obedient, a kindly shepherd unifying the sheep, always ready to listen and comfort. It tries to portray him as apolitical, as if that was possible in 1st century Palestine! Similarly the Church has wanted its leaders to be meek, mild, and obedient, always ready to apolitically pacify and console. ‘Servant leadership’ is the term.

The Church wants to be safe. It wants leaders who will make people feel safe. It asks its leaders to faithfully adhere to the traditions and understandings of the past in the mistaken belief that repetition will bring security. It asks its leaders to care for the members. It asks its leaders to coach and equip the members in caring. And it asks its leaders to care for outsiders - but not at the cost of neglecting the members. Like a well-run club the wellbeing of members is paramount because the highest value in the Church is continuity. Is it accidental then that we appoint people into positions of authority who have highly developed managerial skills?

Jesus wouldn’t have got a job in the Church, and if he had he would have turned it down. The Bible portrays him as confrontational, challenging, and disturbing. He was rude to those in authority. He disregarded the rules. He spent more time with the unfaithful than he did with the faithful. He got into heated arguments and said outlandish things. He had grandiose ideas that didn’t seem to lead anywhere. He was impractical. The bottom line was: Jesus served no one but God. An employee of the club needs to serve the needs of the club.

Jesus was a leader, not a manager.

Good management is essential in any organization. People need to be heard and understood. Good processes, protocols, and safety provisions need to be in place. Conflict needs to be mediated and resolved. Employees and clients’ hopes and expectations need to be taken seriously. Good management usually leads to increased productivity and profit. This is what many people understand to be leadership.

There is no evidence in the biblical texts that Jesus was a manager. There are few stories of him patiently mediating in conflicts between the disciples; or emphatically caring for those who gave up their jobs and businesses to follow him; or sitting down and listening to the hopes and fears of his followers. Commentators who believe Jesus pastorally coached his disciples are largely arguing from what is unsaid in the texts rather than what is said.

However there is no doubt in anyone’s mind that Jesus lived and preached a vision, and challenged others to follow him.

I think the Church has a bad habit of trying to domesticate Jesus. It paints him as meek, mild, and obedient, a kindly shepherd unifying the sheep, always ready to listen and comfort. It tries to portray him as apolitical, as if that was possible in 1st century Palestine! Similarly the Church has wanted its leaders to be meek, mild, and obedient, always ready to apolitically pacify and console. ‘Servant leadership’ is the term.

The Church wants to be safe. It wants leaders who will make people feel safe. It asks its leaders to faithfully adhere to the traditions and understandings of the past in the mistaken belief that repetition will bring security. It asks its leaders to care for the members. It asks its leaders to coach and equip the members in caring. And it asks its leaders to care for outsiders - but not at the cost of neglecting the members. Like a well-run club the wellbeing of members is paramount because the highest value in the Church is continuity. Is it accidental then that we appoint people into positions of authority who have highly developed managerial skills?

Jesus wouldn’t have got a job in the Church, and if he had he would have turned it down. The Bible portrays him as confrontational, challenging, and disturbing. He was rude to those in authority. He disregarded the rules. He spent more time with the unfaithful than he did with the faithful. He got into heated arguments and said outlandish things. He had grandiose ideas that didn’t seem to lead anywhere. He was impractical. The bottom line was: Jesus served no one but God. An employee of the club needs to serve the needs of the club.

11/02/2006

Guy and the Sheik

Guy Fawkes Day is fundamentally not about fireworks, family, and frightened animals. It is about religious dissent. It asks what are appropriate expressions and responses to religious dissent, and whether even today diverse beliefs can coexist in the same society.

Guy Fawkes was born in Yorkshire in 1570 into an upper middle class family. At age 23 he joined the Spanish Army and spent ten years serving on the continent. It was during this time he converted to Roman Catholicism. Upon returning to England he was subjected, like all Catholics, to the repressive decrees instituted by Elizabeth and continued by her successor James I. One decree passed in 1604, for example, imposed heavy fines on Catholics and confiscated their property.

The prevailing 17th century orthodoxy was that England was Anglican and all other expressions of faith were evidence of allegiance to foreign powers and the doorway to treason. Monarchy, nationalism, race, and religion were blended into one. Plurality was not tolerated, and where difference existed it was persecuted.

When Guy Fawkes and his fellow plotters failed with their explosive plan they were hung, drawn, and quartered. Not content to punish just a few the authorities rounded up thousands of innocent Catholics and imprisoned them too. In the paranoiac traditions of religious scapegoating Guy was called the “Great Devil”, and for centuries his stuffed effigy was annually burnt on November 5th. Only in recent years has ‘burning the Guy’ gone out of fashion.

The delineation of the world into goodies and baddies, and good and bad religion, is unfortunately all too common. Fed by the surety of conviction, and satisfying the simple-minded with the promise of security, it has led to the justification of all manner of violence towards those who believe differently. Persecuting religious dissent is a symptom of a weak society, unsure of itself and thus defensive.

Sheikh Alhilali is a close-to-home example of religious dissent. His views to the sensibilities of most are repugnant. ‘Misogynist’, ‘anti-Semitic’, and ‘supporter of Islamic insurgents’ are all labels that have been stuck on him, and not without some justification. He and his supporters protest that he is misunderstood. Most Australians and New Zealanders though can recognise bigotry in religious drag. Anglicans know plenty of examples from our religious past and present!

In the deservedly strong response to the Sheikh’s comments there is a significant number who want to gag him. If the Muslim community to which he is accountable want to censor him that is one thing. When politicians however suggest revoking the Sheikh’s permanent residency status and deporting him that is something else. We need to ask whether we believe in a society where strong and offensive viewpoints can be exchanged.

I don’t want to live in a homogenized society where viewpoints are always sanitized before publication. Bigotry will always be among us. When expressed it is ugly. Yet it won’t go away by muting or banning it. Bigotry needs to be confronted by the reason and experience of others.

Religious history is peppered with the repression of minorities. Some groups within these minorities occasionally responded with violence, like the Gunpowder Plotters. No civil society can tolerate that. However civil society can treat minorities equally before the law and allow minority views to be aired – even the obnoxious ones. It can also then share one of the great gifts of a secular democracy by criticising those obnoxious beliefs to hell.

10/27/2006

Is God a cat?

If you are not a dog/god fan read this from my friend Celia's feline:

Is God a Cat?

One of the oddest things about humans is the way they anthropomorphise their God. If you listen to them talking about God (any main religion god) you get a picture of a sort of super human - almost always male, a person, a father, a director, sometimes even new employer. My thoughts were prompted from sitting on Celia's desk reading the blog of Ruth Gledhill of the Times. It is as if humans can't imagine a God that isn't human. I say what if She was a Cat. If God was a Cat, things would be different. For one thing, She'd make it clear that some of the human activities had got to stop - trapping and killing cats, shooting cats with air guns, kicking cats, etc. Instead churches would open their doors not just to church mice but to church cats. They'd take collections and go and buy cat food for strays. And all the starving little strays that scrounge a living in busy towns would know there was a sanctuary for them - a dry sheltered place with lots of room and cat food given out free. There'd be less church ritual (what's the point of if?), less standing up and kneeling, less human music (though some caterwauling would be lovely at midnight mass), and more practical charity. Humans would be allowed in to serve others (cats) and, if they persisted with their 'services" (which aren't really anything of the kind in practical terms) we could sit on their warm laps for the duration. Some churches already have their resident felines. At the Tower of London chapel there is Teufel, a black tom who is known for enjoying weddings. He often sits down for a nap on the bride's train. Rupert was assistant organist at St Lawrence, Ludlow. And Lucky is a convent cat. She joins in as the nuns sing Alma Redemptoris Mater. As humans no longer go to church, perhaps we could take over.

Of course, it is pretty bad news for mice if She is a Cat.

And even worse news for us, if God was a Mouse.

http://george-online.blogspot.com

Is God a Cat?

One of the oddest things about humans is the way they anthropomorphise their God. If you listen to them talking about God (any main religion god) you get a picture of a sort of super human - almost always male, a person, a father, a director, sometimes even new employer. My thoughts were prompted from sitting on Celia's desk reading the blog of Ruth Gledhill of the Times. It is as if humans can't imagine a God that isn't human. I say what if She was a Cat. If God was a Cat, things would be different. For one thing, She'd make it clear that some of the human activities had got to stop - trapping and killing cats, shooting cats with air guns, kicking cats, etc. Instead churches would open their doors not just to church mice but to church cats. They'd take collections and go and buy cat food for strays. And all the starving little strays that scrounge a living in busy towns would know there was a sanctuary for them - a dry sheltered place with lots of room and cat food given out free. There'd be less church ritual (what's the point of if?), less standing up and kneeling, less human music (though some caterwauling would be lovely at midnight mass), and more practical charity. Humans would be allowed in to serve others (cats) and, if they persisted with their 'services" (which aren't really anything of the kind in practical terms) we could sit on their warm laps for the duration. Some churches already have their resident felines. At the Tower of London chapel there is Teufel, a black tom who is known for enjoying weddings. He often sits down for a nap on the bride's train. Rupert was assistant organist at St Lawrence, Ludlow. And Lucky is a convent cat. She joins in as the nuns sing Alma Redemptoris Mater. As humans no longer go to church, perhaps we could take over.

Of course, it is pretty bad news for mice if She is a Cat.

And even worse news for us, if God was a Mouse.

http://george-online.blogspot.com

10/13/2006

Entering the Theological Dog-House

If you want to judge a religion firstly judge how many constraints it puts upon God, then judge the religion by its mercy. The untameable God who pushes us beyond our boundaries has always and continues to prod and shove us towards the exercise of mercy and compassion.

Jesus was a reforming Jew who rebelled against love being turned into legalism. His ministry was one of constant and unbridled compassion. Nowadays it seems that many Christian fundamentalists are trying their hardest to turn love back into legalism!

Every religion needs to examine its beliefs to see whether they encourage adherents to be more or less merciful, more or less tolerant, and more or less compassionate. This is the touchstone of faith: does your church make you kinder? Does your church make the world a kinder place? And if it doesn’t my advice is to ditch your church and go looking for God.

Kindness and compassion led St Francis of Assisi well beyond his comfort zone. There is a story told of Francis[1] and a savage wolf. The citizens of Gubbio were wary and frightened to venture beyond the city walls. Francis, both compelled by and trusting in God, went out alone to meet this wolf. The brute appeared. Francis made the sign of the cross and spoke, calling the beast “Brother Wolf” and telling him off for all the suffering he had caused. The wolf, having made ready to pounce, became very quiet, and in the end lay at Francis's feet. The tradition records that “[the wolf from then on] lived in the city ...and was fed by the people ...and never a dog barked at him, and the citizens grieved... at his death from old age.”

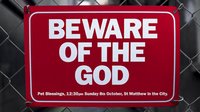

Let us note that, firstly, Francis was pushed by God to confront his fears. He ventured out, beyond where it was safe. Beware of the God. Secondly, Francis engaged with the wolf that others both feared and excluded. Risky behaviour. Thirdly, he brokered a deal that was of mutual benefit to both the wolf and the townsfolk, and built a lasting connection between them.

There was another solution available to the citizens of Gubbio: hire a hunter to kill the wolf. Time and again this has been what humans have done. Rather than befriend our fears we have killed that which has threatened us. It has led to the depletion and extinction of many animal species. It has led to many wars and generations fed by hatred. The story of the Wolf of Gubbio, on the other hand, invites us into building relationships of trust and mutuality with those we fear.

There are similar Francis stories around poverty and sickness – like when he hugged a leper; and around enemies and Islam – like when he visited the Sultan of Babylon. Each of these stories is about Francis being pushed by God beyond the limits of safety to embrace humans or animals others were frightened of and wished to exclude or destroy.

Our actions towards animals, or towards those who are labelled as deviant or different, or towards those with little status or power, or towards those of other religions or none… is the measure of our faith. This is not an easy or comfortable faith. Frequently you will find yourself consigned to the theological dog house. By siding with outsiders you become an outsider yourself. Ask Francis. Ask Jesus. Ask God.

[1]Almedingen, E.M. Francis of Assisi: A portrait, The Brodley Head: London, 1967.

10/08/2006

Beware Of The God

“Beware of the God” reads the bright red sign outside our church. The kennel beneath it and the subscript advertising the upcoming animal service give the sign its context. Adults and children smile as they pass by.

Our detractors also love it. “Ah,” said one chap last week grinning at the thought, “at last, a theological health warning outside St Matthew’s.” He thinks visitors should be wary of the God within.

I agree with him. The God we worship here is not safe, and will not make you safe.

There is a deep Hebraic truth that God cannot be contained or tamed by our desires to have an orderly, secure, and predictable life. What Christianity often does to God is what Governor Reagan of California in the 1970s tried to do to the Redwoods, namely make them into lounge furniture. That which is wild, wonderful, and free is an affront to our worst managerial instincts. It needs to be cut down, domesticated, and made into something comfortable to sit on and sip our coffee.

Proponents of Christianity throughout the ages have tried to keep God under control by creating fences out of the Bible, the Creeds, synods, clergy, hymns, and liturgies. Yet, we need to be aware of who and what we are dealing with. For God continually breaks out of our constructs and language - popping up in others’ holy texts, speaking through social and political outcasts, refusing to favour any one race, religion, or sexual orientation, and generally being a darn nuisance to those who like decency and order. Be aware, this God is not safe.

If you want to judge a religion firstly judge how many constraints, collars, leashes, and fences it puts around God.

p.s. check out Deborah's site in the land of Oz www.bewareofthegod.com

10/03/2006

What do you see?

"There was once a holy man in India who lived in prayerful state – so much so that everyone thought he was nuts. One day, having begged for food in the village, he sat by the roadside and began to eat, when a dog came up and looked at him hungrily. The holy man then began to feed the dog; he himself would take a morsel, and then give a morsel to the dog as though he and dog were old friends. This was an extraordinary sight in this part of India at the time. People with nothing didn't share their food with dogs! Soon a crowd gathered to watch.

One of the men in the crowd jeered at the holy man. He said to the others, "What can you expect from someone so insane that he is not able to distinguish between a human being and a dog?"

The holy man replied, "Why do you laugh? Do you not see Jesus seated with Jesus? Jesus is being fed and Jesus is doing the feeding. So why do you laugh, oh Jesus?"

This is a story about vision, about what you see. One could see just an old man foolishly giving what he cannot afford to give to a dog. This way of seeing invites one to either deride or reprove the old man. On the other hand, one could see that God or Jesus is in everyone – the man, the dog, the spectators, and even you. This way of seeing invites one to treat every living creature as holy and worthy of respect and dignity.

One of the men in the crowd jeered at the holy man. He said to the others, "What can you expect from someone so insane that he is not able to distinguish between a human being and a dog?"

The holy man replied, "Why do you laugh? Do you not see Jesus seated with Jesus? Jesus is being fed and Jesus is doing the feeding. So why do you laugh, oh Jesus?"

This is a story about vision, about what you see. One could see just an old man foolishly giving what he cannot afford to give to a dog. This way of seeing invites one to either deride or reprove the old man. On the other hand, one could see that God or Jesus is in everyone – the man, the dog, the spectators, and even you. This way of seeing invites one to treat every living creature as holy and worthy of respect and dignity.

9/27/2006

Beyond Pluto

In ancient times the word ‘planetai’, meaning wanderers, was applied to the seven heavenly bodies that moved. They couldn’t see Neptune and Pluto. Also, being pre-Galileo, it was assumed the sun was one of the seven and the earth wasn’t. The definition of planet was therefore not fixed but was to be influenced by changes in science and thinking in the years ahead.

This is not so different from the Christian history of God. Within the pages of the Bible God progresses from being a personal deity, to a tribal deity, to a deity who was pan-tribal, to one that transcended all human constructs. The location of God moved from the desert, to the Temple, to a literal realm in the sky, to the presence of the historical Jesus. Later in the early centuries of Christianity, via an intricate weaving of Greek and Hebrew thought with the experience of transformative love in Jesus, God was woven into the tapestry called Trinity. But the development of God didn’t stop there, locked in the 4th century. God as ‘process’, as ‘go-between’, as ‘liberator’, as ‘matrix of grace’… were all still to come.

The influence of science and philosophy on the definition and development of God is not to be underestimated. Indeed it is the interplay between experience, history, and science that has pushed at and shown as puny the simplistic notions of God.

God is a word that defies close definition. Language being a system of signs and codes is based around the visible and tangible. When language has to be found for the invisible and intangible then multiple metaphors are used. We say the thing we are trying to describe is something like this, but also not like that. It is also something like this, but also not like that. No one set of metaphorical clothes quite fits. In theology we surmise that such is the nature of God that no sets of clothing will ever quite fit.

The other word in theology that defies close definition is soul. Soul, or ‘heart’ as it’s sometimes called, is an attempt to talk about God in us and us in God. It blends passion, feeling, wisdom, and wholeness. A person can gain the whole universe, be as rich and successful as he or she could possibly imagine, yet without attending to their soul they gain nothing. To nurture the soul, the task of spirituality, is therefore very important. All sorts of little things help – walking in the bush, conversing with a child, smelling the coffee before you drink it, laughing often… Yet answering the question of why these things help is harder. It is as if the universe is inside us, and all the spinning, pulling, moving and amazing wonders need to be held together in some way.

When I was a teenager I spent many nights each year sleeping under the stars. There is nothing quite like falling asleep beneath an enormous canopy of twinkling lights, variously arranged, and different each evening. Being a child of modernity I knew that the blackness of the sky was not a great dome that encompassed the earth and above which a kingly God sat. I knew the blackness was all I could see of the fathomless depth beyond, where the experience we call God might or might not be. For everything that astronomy could tell us there was always more it couldn’t. Yet, like the best of theology, its purpose was to ignite wonder and imagine limitless possibility.

Should Pluto be relegated? The debate will continue for some time yet. The pragmatists will probably triumph over the purists. They usually do. Yet the former need to be cognisant that their revised definition will in time also change. Heavenly bodies are not always what they seem.

This is not so different from the Christian history of God. Within the pages of the Bible God progresses from being a personal deity, to a tribal deity, to a deity who was pan-tribal, to one that transcended all human constructs. The location of God moved from the desert, to the Temple, to a literal realm in the sky, to the presence of the historical Jesus. Later in the early centuries of Christianity, via an intricate weaving of Greek and Hebrew thought with the experience of transformative love in Jesus, God was woven into the tapestry called Trinity. But the development of God didn’t stop there, locked in the 4th century. God as ‘process’, as ‘go-between’, as ‘liberator’, as ‘matrix of grace’… were all still to come.

The influence of science and philosophy on the definition and development of God is not to be underestimated. Indeed it is the interplay between experience, history, and science that has pushed at and shown as puny the simplistic notions of God.

God is a word that defies close definition. Language being a system of signs and codes is based around the visible and tangible. When language has to be found for the invisible and intangible then multiple metaphors are used. We say the thing we are trying to describe is something like this, but also not like that. It is also something like this, but also not like that. No one set of metaphorical clothes quite fits. In theology we surmise that such is the nature of God that no sets of clothing will ever quite fit.

The other word in theology that defies close definition is soul. Soul, or ‘heart’ as it’s sometimes called, is an attempt to talk about God in us and us in God. It blends passion, feeling, wisdom, and wholeness. A person can gain the whole universe, be as rich and successful as he or she could possibly imagine, yet without attending to their soul they gain nothing. To nurture the soul, the task of spirituality, is therefore very important. All sorts of little things help – walking in the bush, conversing with a child, smelling the coffee before you drink it, laughing often… Yet answering the question of why these things help is harder. It is as if the universe is inside us, and all the spinning, pulling, moving and amazing wonders need to be held together in some way.

When I was a teenager I spent many nights each year sleeping under the stars. There is nothing quite like falling asleep beneath an enormous canopy of twinkling lights, variously arranged, and different each evening. Being a child of modernity I knew that the blackness of the sky was not a great dome that encompassed the earth and above which a kingly God sat. I knew the blackness was all I could see of the fathomless depth beyond, where the experience we call God might or might not be. For everything that astronomy could tell us there was always more it couldn’t. Yet, like the best of theology, its purpose was to ignite wonder and imagine limitless possibility.

Should Pluto be relegated? The debate will continue for some time yet. The pragmatists will probably triumph over the purists. They usually do. Yet the former need to be cognisant that their revised definition will in time also change. Heavenly bodies are not always what they seem.

9/26/2006

To Pluto

“Honk if you love Pluto” declares the T-shirt. Not too dissimilar from the ones promoting honking for Jesus. And, like so often happens with discussing heavenly bodies, the Pluto debate is up and raging. The International Astronomy Union (IAU) meeting in Prague last month adopted a new definition of a planet – one that knocked Pluto out of the club.

Living on the extremities of planetary imagination - even with the Hubble Space Telescope it is still merely a bleary sphere in shades of grey - Pluto didn’t join the club until 1930. That was the year when a 24-year-old American by the name of Clyde Tombaugh mapped movement where movement had not been mapped before. A young girl from Oxfordshire suggested the name of Pluto, Roman God of the Underworld. Beyond Pluto was the abyss of unknowing.

Since the 1930s Pluto has shrunk. With each advance in technology Pluto’s measurements have diminished. It’s now smaller than our moon. Hence the T-shirts, without the honking, that proclaim ‘size doesn’t matter!’ and ‘is a dachshund not a dog?’

What does matter to the astronomical elites is the discovery in the 1990s of other Pluto-like bodies on the edge of our telescopic vision. And not just one, or five, but hundreds, and probably thousands!

This naming debate has spilled over into popular consciousness. The public wanted a voice. Pluto was not just a bleary dot out in space it is something people love. It inspired and inspires myths, art, and poetry. It is part of astrology charts – ‘Pluto direct’ is a way of talking about transformational energy. Kids identify with Pluto’s smallness. In particular adults who forlornly hope that ‘whatever has been will forever be’ find its demotion out of the Big Nine major league of planets difficult to accept.

The pragmatists of astronomy suggest that instead of knocking Pluto out of the club that the IAU change the rules. In other words expand the definition of planet to include not only the eight and Pluto but also Eris [formerly known as Xena] and Ceres. The purists though argue that this will open the doors to hundreds maybe millions of potential new planets. This is a debate about not only who can join the club and who controls who joins the club, but also the fear of loosing control of the boundaries. Sounds very much like Christianity me!

Living on the extremities of planetary imagination - even with the Hubble Space Telescope it is still merely a bleary sphere in shades of grey - Pluto didn’t join the club until 1930. That was the year when a 24-year-old American by the name of Clyde Tombaugh mapped movement where movement had not been mapped before. A young girl from Oxfordshire suggested the name of Pluto, Roman God of the Underworld. Beyond Pluto was the abyss of unknowing.

Since the 1930s Pluto has shrunk. With each advance in technology Pluto’s measurements have diminished. It’s now smaller than our moon. Hence the T-shirts, without the honking, that proclaim ‘size doesn’t matter!’ and ‘is a dachshund not a dog?’

What does matter to the astronomical elites is the discovery in the 1990s of other Pluto-like bodies on the edge of our telescopic vision. And not just one, or five, but hundreds, and probably thousands!

This naming debate has spilled over into popular consciousness. The public wanted a voice. Pluto was not just a bleary dot out in space it is something people love. It inspired and inspires myths, art, and poetry. It is part of astrology charts – ‘Pluto direct’ is a way of talking about transformational energy. Kids identify with Pluto’s smallness. In particular adults who forlornly hope that ‘whatever has been will forever be’ find its demotion out of the Big Nine major league of planets difficult to accept.

The pragmatists of astronomy suggest that instead of knocking Pluto out of the club that the IAU change the rules. In other words expand the definition of planet to include not only the eight and Pluto but also Eris [formerly known as Xena] and Ceres. The purists though argue that this will open the doors to hundreds maybe millions of potential new planets. This is a debate about not only who can join the club and who controls who joins the club, but also the fear of loosing control of the boundaries. Sounds very much like Christianity me!

9/19/2006

Colouring The City

Sun breaks through the clouds

Igniting the rain-drenched road.

The world looks new

Washed and gleaning

Glistening as the fairies dance.

Pink is a powerful colour

Favoured of the young princess

Pirouetting in the privacy of her room.

Yet it is largely absent from the tie racks

of downtown business.

Colour is political in the city

Blue and red compete for allegiance

Green is a brand without a billboard.

Brown, bent, and cold are

the colours of poverty.

The fairies dance up the road

Dodging the traffic, slurs, and unbelievers.

Only little children hold their breath as

imagination confronts the colours

offering an inkling of hope.

The hope of the city is found in the contrasts – of ideology, beliefs, people, and colour.

Igniting the rain-drenched road.

The world looks new

Washed and gleaning

Glistening as the fairies dance.

Pink is a powerful colour

Favoured of the young princess

Pirouetting in the privacy of her room.

Yet it is largely absent from the tie racks

of downtown business.

Colour is political in the city

Blue and red compete for allegiance

Green is a brand without a billboard.

Brown, bent, and cold are

the colours of poverty.

The fairies dance up the road

Dodging the traffic, slurs, and unbelievers.

Only little children hold their breath as

imagination confronts the colours

offering an inkling of hope.

The hope of the city is found in the contrasts – of ideology, beliefs, people, and colour.

Drinks on the House

Jesus on a beerglass to spearhead Christmas campaign - ekklesia news service 14/09/06

A Christmas poster campaign aimed at getting people talking about God is to feature a picture of Jesus on a beer glass.The image of Jesus in the froth left on the sides of an almost empty pint glass next to the words 'Where will you find him?' will spearhead the Churches' Advertising Network (CAN) initiative.